Designing Conversations that Lead to Action

At Moneythink, we empower under-resourced students by supporting financial decision-making through coaching and technology. Our coaches message students over text — giving rapid access to quality support. We have spent years working with students and we have learned about the art of designing conversations with them that lead to positive, empowered action on their college journey.

Why Designing Conversations is Important

These are the kinds of text messages we get daily.

Only 9% of low-income students receive their college degree within four to six years. The main barrier to a degree is money. Low-income students are left on their own to navigate complex financial aid systems and make some of the biggest financial decisions of their lives.

Because of warm-fuzzy texts like this (and the results of qualitative and quantitative data analysis), we are gaining confidence in our hypotheses about the best ways to give students more confidence, more financial security, and less stress. Over the past year of texting, we have honed in on a set of principles that guide the experience and voice of our coaching.

Our Guiding Principles

In this share-out, you will find just a few of some of our most powerful and, sometimes, non-obvious principles for designing conversations. You might find these particularly interesting if your team is designing…

- For a chatbot, human-powered messaging service, or a hybrid,

- A coaching service (especially in health or finances),

- For under-resourced populations that face scarcity,

- Interventions for behaviors that have low desirability (getting people to do something they don’t want to do).

Under-resourced students already experience scarcity of time, money, calories, sleep, and sometimes even shelter. Their cognitive bandwidth is spent mentally managing these resources.

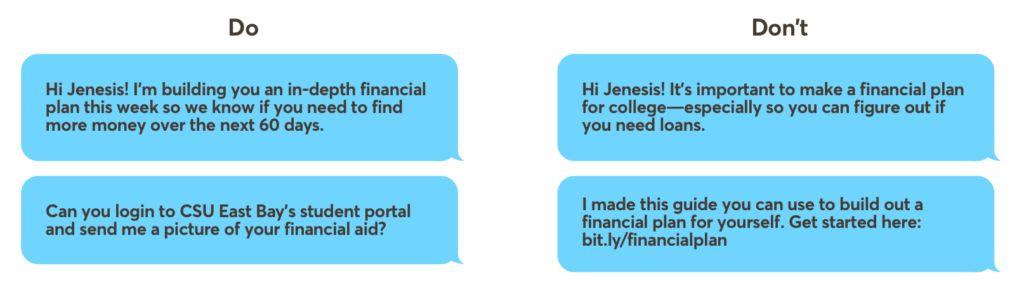

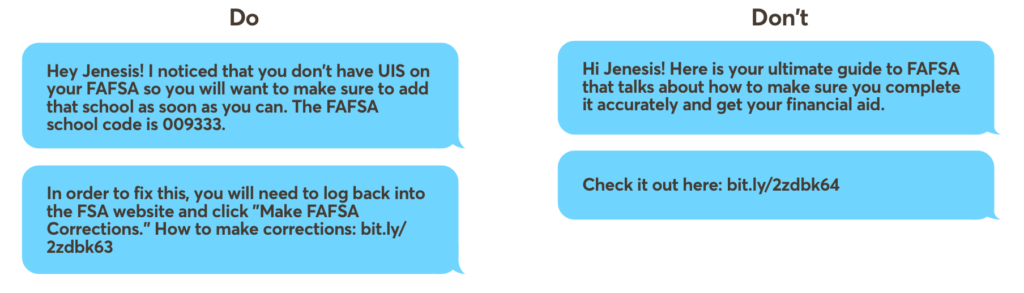

We identify the most critical financial barriers on the pathway to college and do everything we can to minimize those barriers for the student.

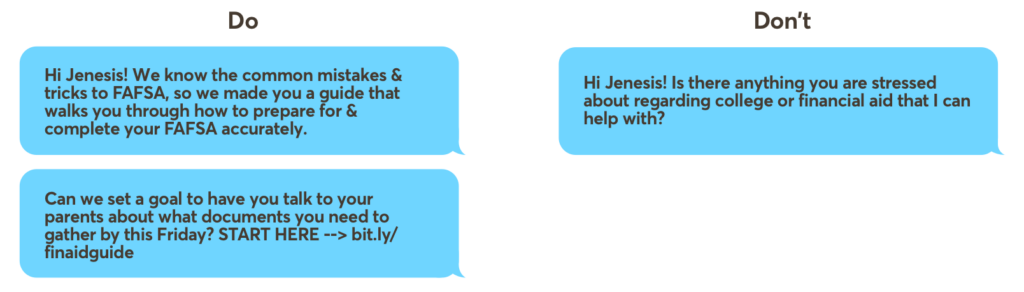

Don’t wait for a student to guide the interaction, share goals, or suggest deadlines.

Recommend to the student the goal they should be working on next and default them into a deadline.

Make it just as easy for a student to communicate wins.

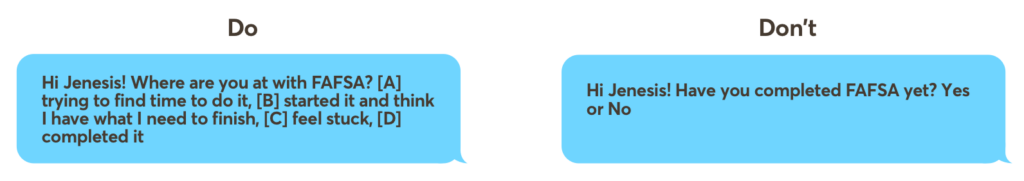

Never ask a student to answer a question where their answer makes them reflect negatively on their self-identity.

Nudge the student to complete a reasonable, small task and provide the support and information they need to complete the task.

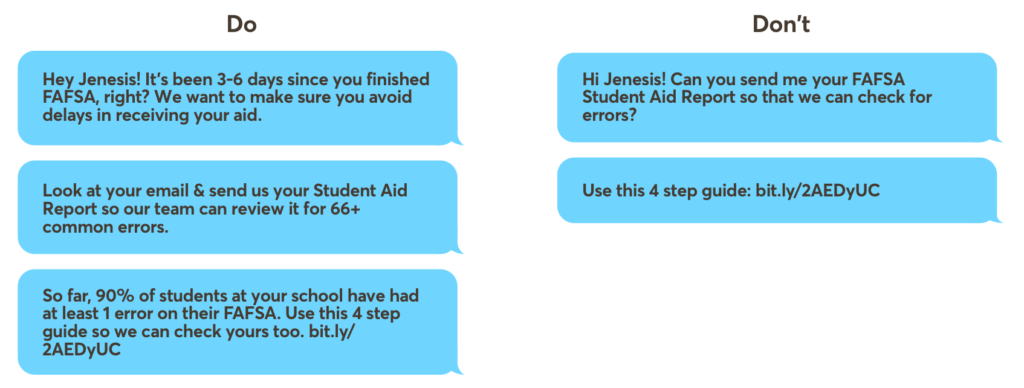

Use behavioral science levers to instill a sense of urgency. For example:

- Defaulting students into deadlines that are three to five days away as opposed to weeks away (limited attention)

- Suggesting that recommended behaviors are a norm of their peers (social proof)

- Making long-term negative consequences tangible in the immediate to trigger FOMO (loss aversion).

Designing Conversations: Principles

Good principles are ones that the team uses actively.

- Principles feel the most helpful when they are specific and speak to how to handle trade-offs. Jared M. Spool wrote a great article on “Creating Great Design Principles.”

- Leverage behavioral science — especially if you are designing for behavior change. Check out ideas42’s list of behavioral principles to get started.

- Just start! Let your principles mature as you regularly use them and iterate. The list of principles we have now are non-obvious — they have come from tons of exposure hours texting and talking with our students.

- Remember that the goal of developing principles is not to have a perfect, finished artifact.

- The goal is to enable the team to have a common language for weighing design possibilities in a way that stays grounded in our user’s reality.

- Good design principles enable healthy discourse and are owned and contributed to by everyone who has a hand in building the user experience.

Working on something similar? Reach out and tell us about it. We love to learn with others.

Learn more about Moneythink’s approach to design and reach out to say hello! Transformative progress requires leaders in technology, data, and design to work together. We work out of San Francisco & Oakland and we love making friends with other humans who believe in the power of design and are obsessed with building a more equitable future.